Patients usually do not think of dentistry as being of low risk or high risk from a medical perspective. When visiting the dentist, a patient would expect that the dentist knows exactly what he or she is doing and that it is relatively safe to undergo the treatment proposed. Most dentists graduate with an understanding of the basic concepts of general dentistry and are fully capable of performing a wide array of treatments. In my humble opinion, the problem of risk lies in the nature of dentistry itself, and I have spent a great deal of time thinking about this.

Let us consider the profession. Dentists come in many different forms: cosmetic dentists, prosthodontists, periodontists, orthodontists, endodontists, general practitioners, oral surgeons, implantologists, paediatric dentists and others. It is difficult for the public to differentiate one from the other, and moreover, a general practitioner (GP) can perform most dental procedures if well trained. Let us look at it this way: when a patient goes to the hospital, he or she is directed to a specialist in the part of the body that has the problem. That specialist is usually highly trained and has the resources in his or her department to treat that part of the body. You will never see a medical GP operating on a patient’s heart or an orthopaedic surgeon operating on a patient’s brain.

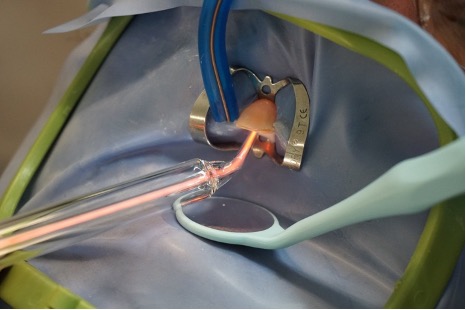

Use of platelet-rich fibrin to accelerate wound healing after extraction and to avoid alveolitis. (Image: Miguel Stanley)

Like the body, the oral cavity should be seen as consisting of parts: hard tissue, soft tissue, nerves, bone, teeth, mechanics and muscles. A myriad of problems can occur in the oral cavity. You can have biological issues such as infections, mechanical issues such as fractures or abrasions, and of course, your teeth create one of the most important things connected to our emotions: the smile. So why should we expect a GP to solve all these problems?

To make matters more complicated, any dentist is legally allowed to perform hundreds of different procedures. From a simple cleaning all the way up to extracting every single tooth in a patient’s mouth and replacing them with dental implants and new laboratory-made teeth. This is actually quite a crazy concept when you think about it. It is like having a driver’s licence that will allow you to drive a motorbike, a car, a truck, an 18-wheeler, an aeroplane and a jet. It is very unlikely that anyone could be good at all these things.

This is a global phenomenon, and it is no different in the US, despite having very specialised dentists in each discipline. Recent studies show double-digit growth of the GP market in terms of implantology, orthodontics and cosmetic dentistry that are now powered by digital technologies such as digital smile design, clear aligners and guided implant surgery. In a recent analysis published by the American Dental Association’s Health Policy Institute, of the 198,517 practising dentists in the US in 2017, 156,992 (the majority at 79%) are GPs, 7,546 oral and maxillofacial surgeons, 5,664 endodontists, 10,658 orthodontists, 7,778 paediatric dentists, 5,790 periodontists and 3,708 prosthodontists, and 426 work in oral and maxillofacial pathology, 827 in public health dentistry, and 144 in oral and maxillofacial radiology.1 This calculation counts a dentist toward each practice area for which he or she holds a degree. For example, a dentist possessing degrees in orthodontics and paediatric dentistry is counted in both categories. According to these figures, there were 1,007 dentists with multiple specialty degrees. Nevertheless, although dentists tend to obtain a specialty degree, if we compare the number of general dentists to the number specialists in 2001 and 2017 in the US, there is evident growth in the number of GPs: from 130,775 in 2001 to 156,992 in 2017.1 The most popular specialty in the US is orthodontics, and in 2001, there were 9,265 orthodontists, compared with 10,658 in 2017.1

“I believe that the development of technologies will help and assist GPs and less skilled dentists to perform high-quality dentistry.”

Since there is no true quality control oversight in dentistry except for our personal ethics, if the patient demands a procedure that the dentist is legally licensed to perform, but technically inexperienced in doing so, yet there is a financial reward for conducting it, the risk of things going wrong is quite high. This begins to explain the fine line between high-risk and low-risk dentistry.

The American Academy of Oral Medicine (AAOM) developed a risk assessment that affirms that the patient evaluation process requires inclusion of determination of risk associated with dental treatment, as it is essential for the delivery of safe and appropriate dental care as well as the overall health of the patient. AAOM classifies high-risk treatments according to the patient’s age and the potential for infections and complications, among others.2 Nevertheless, it does not consider the experience of the treating dentist, the technologies that the clinician is using or even the time the dentist has in which to perform the treatment.

In dentistry, it is my understanding that the higher the degree of complexity of treatments you carry out, the more technology and materials you need, and the more experienced and trained your team must be. For this reason, most clinics that offer high-end dentistry usually have a large team and invest significantly in technology and materials.

Once you move into the realm of dental aesthetics, you are entering into an emotional relationship with your patient; unless you are able to deliver what the patient desires, you will encounter complications down the road. It requires an expert cosmetic dentist and a great dental technician to ensure that the patient is happy. I consider most complex aesthetic dental work in the anterior area to be high risk in nature.

Use of dental dam isolation and ozone therapy to guarantee elimination of any bacteria. (Image: Miguel Stanley)

Implant dentistry has been growing in double digits for years, around the globe. It is not something that should be taken on lightly and requires a great deal of training and technology. No matter how simple a procedure might be, I consider this field to be high risk. There are so many things that can go wrong, and the fact that in many cases the surgeon is not the one doing the restorative work can lead to complications. All it takes is poor positioning of the implant to really create a huge headache for the restorative team. When things go wrong, who is to blame? Restorative work too is high risk, but thankfully, digital technologies are here to provide better solutions to this problem with guides and immediate preoperatively milled temporary restorations.

Complex root canal therapy usually requires a microscope, expensive rotary instruments and a highly trained professional, and it can sometimes take many hours to ensure the correct quality of an endodontic treatment. Consider root canal therapy of a second molar with five canals and a complex anatomy. This cannot be seen as a simple procedure, and so I consider this to be a high-risk dental treatment. There are obviously, by this measure, many more interventions that can be considered high risk in nature; the ones I have given are a just a few classic examples.

Low-risk dentistry refers to all the procedures that a relatively inexperienced dentist, as long as he or she is given the necessary amount of time for treatment and the right instruments and technology, can perform with relative safety for the patient and with an optimal outcome from a clinical standpoint. This of course only happens when following a gold standard protocol.

Some examples are:

- Simple direct restorations: when using dental dam isolation and respecting the right bonding steps, manipulation and photopolymerisation of the composite, and occlusal adjustments

- Simple extractions: when employing an atraumatic technique, performing the right curettage, eliminating infection if present, and giving the right postoperative recommendations for optimal healing and thus avoiding complications such as alveolitis

- Oral hygiene: when employing the right diagnostics, performing the correct steps to ensure all calculus and biofilm are removed, and motivating the patient to maintain a good oral health—these things take time, as stated in the Slow Dentistry philosophy

Use of Tekscan technology to obtain a more precise adjustment of the occlusion in oral rehabilitation. (Image: Miguel Stanley)

- Bleaching in office and with take-home trays: when using the right concentration of the bleaching product and following the recommendations of the manufacturer

- Emergency root canal therapy: when using dental dam isolation and performing proper cleaning and instrumentation of the canal

- Crowns and bridges: when following the right guidelines and procedures of preparation, impression taking, cementation and occlusal adjustments, not to mention fit.

Of course, also included are any other procedures that have little impact for the patient or the dentist if things go wrong and for which arising problems can be easily remedied. I see so many simple restorations create such huge headaches due to rushed treatment and a poor protocol.

Nevertheless, although complex risky procedures should be performed by highly trained dentists, nowadays, with the development of new technologies in the dental field, it is easier to perform high-quality complex dentistry even if you are a GP without a specialty degree.

One the one hand, it is important to understand that it requires time to learn how to use technologies in the dental practice and manage costs, and dentists should not consider a quick training session from a sales person to be the same as a proper accredited course.

Technologies such as intra-oral scanners and microscopes are important tools that facilitate our work as dentists, helping us perform more precise work. Nevertheless, both require time to learn to use them properly. (Images: Miguel Stanley)

On the other hand, the dentist’s experience and knowledge as well as the application of high-quality materials at the right time can be influencing factors in the performance of dental treatments, making them more or less risky. One example is the placement of a crown or bridge, even if it is out of the aesthetic zone. This is a common procedure that has all the risk factors. If the dentist knows how to employ a minimally invasive approach, such as Pascal Magne’s,3 using high-quality materials, has the requisite time for treatment and works with a great laboratory, what would otherwise have been considered a high-risk treatment would then be a low-risk one.

To sum it all up, I believe that the development of technologies will help and assist GPs and less skilled dentists to perform high-quality dentistry. Things are rapidly progressing, and artificial intelligence is coming to help us better diagnose and plan. Yet, for those like myself who are managing teams and trying to get the best out of each clinician, from the planning of a treatment sequence, which is key to achieving perfect results, we can now rely on the cloud to help us work with teams in other parts of the world, and delegate responsibilities by ensuring that the quality of the treatment plan is perfect.

I believe that, if dentists work in teams, surrounded by good materials and technology, they can work more safely and practise higher-quality dentistry as a standard. It is up to universities to ensure that the ethical boundaries of business practice and dental practice are never blurred. Science and dentistry must always win over pure profit, and a well-managed team can do both.

Editorial note: A list of references is available from the publisher.